Almost as many Americans (138) were killed at the Battle of Eutaw Springs, South Carolina on September 8, 1781 as were killed at Bunker Hill (140).The British suffered 85 killed (they lost 226 at Bunker Hill) and 351 wounded (to 828 at Bunker Hill). American wounded 375, more than the 271 at Bunker Hill. Eutaw Springs serves as a bloody bookend to the war at the tail end, around the time of Yorktown.

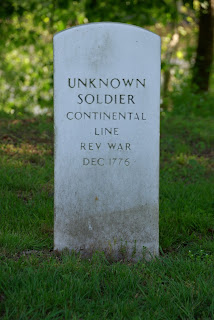

American General Nathanael Greene, having lost his assault on Ninety-Six, continued to harass the British as their forces consolidated in South Carolina at Charleston. British Colonel Alexander Stewart was in charge of the British forces at Charleston, following Lord Rawdon's return to England. He took 2,000 men to search for Greene's army and while camped at Eutaw Springs, Greene attacked him with about 2200 men. Though his men drove the British back and should have won, they started plundering the British tents. The British made a well-defended stand around a brick house near the river, under command of Major John Marjoribanks, and turned the tide against the Americans. Marjoribanks was killed and is buried on the site, shown here.

American General Nathanael Greene, having lost his assault on Ninety-Six, continued to harass the British as their forces consolidated in South Carolina at Charleston. British Colonel Alexander Stewart was in charge of the British forces at Charleston, following Lord Rawdon's return to England. He took 2,000 men to search for Greene's army and while camped at Eutaw Springs, Greene attacked him with about 2200 men. Though his men drove the British back and should have won, they started plundering the British tents. The British made a well-defended stand around a brick house near the river, under command of Major John Marjoribanks, and turned the tide against the Americans. Marjoribanks was killed and is buried on the site, shown here.

(NJ).jpg)

(NJ).jpg)

(NY).jpg)

+(PA).jpg)

(PA).jpg)

(VA).jpg)

+(NY).jpg)

(NC).jpg)